|

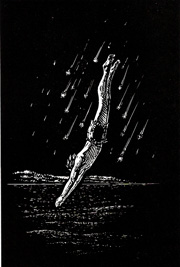

Night of the Falling Stars

or, The Apotheosis of my Brother Jim Summer 2003

That evening we lounged on the afterdeck and watched the night slither in across the moors and low hills to our west. The wind dropped after dark, and the waters of the cove merely riffled against the hull. We could hear frogs and the occasional croak of a night-heron, and then, one by one, from all across the island, whip-poor-wills began to call. It was hot, a sultry night, with the tribes of stars floating overhead and our little vessel suspended between the unfathomable depths of black waters below and black skies above. By this time on our cruise, having been alone for so long, and living as we were under the open skies, my brother began to imagine that we had descended from some lost race of lean bronzed gods, capable of anything. From time to time, in order to prove this fact to visiting sailorettes, my brother had developed the habit of ascending the mainstays, standing on the crosstrees, and then diving headlong from the topmast of the schooner, barely clearing the gunnels in the process. Now, in the close stillness and the flickering heat lighting from the distant shores, he announced that he was going for a swim and began clambering up the mainstay. I watched as his dark monkeylike form shimmied higher and higher. Just before he reached the crosstrees, a shooting star arched out of the black sky over his head and burnt itself out. He gained his foothold and stood upright, steadying himself with one hand on the topmast. Then he raised his arms above his head and balanced momentarily. Two more stars flared out and disappeared. He crouched slightly, raised himself up, and then like a gannet, he speared outward and downward. It was a good dive, one of his best. He seemed to fall in slow-motion, and as his outstretched figure moved across the sky and the black shores, a host of shooting stars, one after the other, dashed out above him. He sailed forward, unbounded, as if he had somehow slipped the chains of gravity, and for a moment it seemed to me that all time was contained between the waters and the stars. He had in fact converted himself into some form of celestial being, one of his lean gods. All around him, as he dove, he trailed stars, a veritable explosion of light. The stars descended with him toward the black depths of the cove, and, when he struck, they followed him into the depths in a great trailing curtain of light, denser now and more brilliant. It was only when I saw his submerged figure halt, turn, and begin rising again, splaying stars outward with every stroke, that I realized he was spilling off phosphorescent plankton and not celestial bodies. Later, much later, and in more boring adult hours, I learned that we had lain in that dark harbor at the height of one of the best Perseid meteor showers in decades. Likewise, the stars of the lower depths were caused by bioluminescence resulting from the excitation of cells of tiny dinoflagellates that move within the sun-warmed waters of New England each year in late summer. But all that, in the end, is mere science, and in those brighter years he and I lived outside of the confines of science and reality—or so we believed. JHM |