|

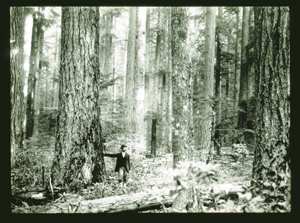

The Forest Primeval

Winter 2003-2004

The fact that a deep and dangerous forest would characterize the outskirts of Hell is not illogical, at least not to the thirteenth-century European mind. It was after all, here, beneath a great overarching canopy of ancient trees, that modern humans first forged the myths, legends, and religions that until fairly recently played such an important part in the human experience. And from the beginning, folktales and legends make it apparent that the relationship between the forest and the peoples who lived in or near it was complicated. The Sumerian epic Gilgamesh, the first written narrative, which was set down no doubt from the stories of a much earlier era, is a case in point. In the epic tale, the hero Gilgamesh befriends a half-man half-animal being named Enkidu. Working together, these two defeat a hideous wild creature named Humbaba, the guardian of the vast cedar forests outside of the city of Uruk. Once the monster is dead, in order to celebrate the victory, Gilgamesh proceeds to cut down the wild forest where Humbaba lived. And so begins Western civilization. By fifth century BC, Plato was already lamenting the loss of the pine forests of the mountains of Greece, and there is good evidence that by the time of the Roman Republic, some 400 years later, most of the native forests of the Italian peninsula, save for a few remote mountain valleys, had been cleared. But the old legends, gods, and demigods from this earlier forested environment were alive and well in the clear light of fifth- century Greece. In one myth from early in Greek history, a young forest nymph who lived in the wilds of Arcadia was courted by the god Mercury. In due time she gave birth to the god Pan, who, not unlike Enkidu, was half-animal half-human. He had the face and upper body of a man but the shaggy legs, hooves, and horns of a goat. According the legends, Pan’s mother was so afraid when she first saw him, she ran away. But Pan grew up to become one of the most entertaining and popular of the Greek and Roman gods and served as a sort of intermediary between wild nature and human settlement. The Lord of the Wood, as he was called, haunted the forested mountain passes above the pastured lands of Arcadia and struck fear into travelers who passed through the ridges at night. You didn’t even have to see him to know he was there; you could feel his presence in the form of “panic.” Pan is the only Greek and Roman god who actually died; all the others merely faded away. At the time of the birth of Christ, or, in some versions of the legend, at the crucifixion, pilgrims traveling in Italy heard a thundering voice echoing through the mountains, crying out that the Great God Pan was dead. This news was followed by wails of lamentation as all the nymphs and dryads and fauns and satyrs, all the old demigods of trees and springs and groves, retreated to the mountain hideaways to bide their time. After that, it is said that the springs fell dry and the famous oracles no longer prophesied accurately; their keeper, the Lord of the Wood, was dead. Fortunately for the older pagan deities, word of this event never reached as far north as Germany, France, and Scandinavia, where the forest-dwelling tribes still held sway. Many of these tribesmen traced their origins to a great World Tree, the Yggdrasil in Scandinavian mythology, an immense sacred ash tree from which all life sprang. Most of the pagan gods, both the good ones and the bad ones, were forest beings; and the priests and ovates of their religions were inclined to make sacrifices to trees to keep them happy—or at least to hold them at bay. The Druid cults in particular were known to worship in oak groves and at sacred forest springs. By the fourth century AD, as Christian proselytizers moved northward converting the conquered tribes, these once-powerful deities began to diminish in the eyes of their former worshipers, although it took a while for them to decline altogether. One of the prime targets of the Christian missionaries was the environment where these gods once dwelt. In 725 AD, for example, Saint Boniface, as if in remembrance of Gilgamesh, celebrated the Christian victory over the German woodland tribes by personally cutting down the huge sacred Donar oak tree in Hesse, called the Red Jove, thus destroying the heart of the old heathen beliefs. But the old forest spirits did not die easily. In particular Pan, or someone very like him, continued to appear in the night forests beyond the villages. Catholic bishops had the wisdom to transform Pan rather than attempt to deny him, however. It was a known fact, they pointed out to the ignorant heathens, that the enemy of God, the Devil himself, had cloven hooves, a set of goat horns, and a pointy little beard. Even that strategy didn’t work entirely, though. The ancient beliefs were perhaps too deeply engrained in the European psyche to disappear in so short a time. Even into the sixteenth century in rural areas, peasants would leave milk and grains and fruits at the edges of the cultivated fields as offerings to a benign forest dweller called the Green Man, who was half-human, half-beast. As long as he was fed, the Green Man would help little children and guide lost night travelers out from the dark forests. Ironically, given his pagan roots, the Green Man’s image, a full-bearded Panlike character who wore a headdress of ivy and fruits, became a popular icon. His likeness can still be seen carved into altars and pillars of medieval and Renaissance churches. A further irony is that the long aisles of the darkened interiors of the great twelfth-century cathedrals of Europe should so closely resemble an old-growth forest. Rank on rank of straight-trunked pillars soar heavenward in a subdued, raking light into the mysterious canopies of beams, cruxes, and trusses. More to the point is that, in more recent eras, the terminology to describe the beauty of ancient woods reverses the metaphor and makes use of the term “cathedral,” sometimes officially, as in the Cathedral of the Pines in Rindge, New Hampshire. Even closer to the idea is the architect E. Fay Jones’ unique Thorncrown Chapel in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, a soaring wooden structure with 425 windows that is thoroughly integrated with the surrounding woodlands. The American poet William Cullen Bryant more or less summed it up when he wrote: “The groves were God’s first temples.” By the nineteenth century, attitudes toward the wild forest were changing, and this time the transformation took place in an unlikely environment—the newly discovered continent of North America. For the first two hundred and fifty years or so, American colonists made war on the forested hills and valleys of the continent, so much so that there were actual firewood shortages in Boston as early as the eighteenth century. By the midnineteenth century, American writers and painters in search of civilized inspiration were spending their formative years in Rome and Florence, enjoying the pastoral Italian landscapes and the villa gardens outside the cities. One of these sojourners, Ralph Waldo Emerson, was deeply impressed with the then half-ruined, moss-grown gardens at Tivoli and the rural scenery of the Campagna outside Rome. When he returned from his first trip to Italy, the first essay he wrote—Nature—helped to reshape the American attitude toward wild nature and encouraged an acceptance, for spiritual reasons, of wildness per se. During this same period, the American ambassador to Rome, George Perkins Marsh, published a book called Man and Nature, which was essentially the first ecological tract. Basing his theories on his understanding of the environmental history of the Italian peninsula, Marsh effectively documented the fact that human tampering, mainly in the form of deforestation, and not the apparent chaos of wild nature, was the cause of soil erosion, flooding, and other environmental problems. But as far as American acceptance of these two important ideas is concerned, it was the work of artists that encouraged the general public to rethink the forest. A number of painters were living in Rome in the 1830s and painting romanticized canvases of the Italian countryside. One of these, an Englishman named Thomas Cole, came to America and settled in the Hudson River valley where he was awed by the untouched forested environment of the western banks of the river and the Catskill Mountains beyond. Cole believed he had found rich subject material, “a land new to art,” as he phrased it. Cole’s paintings and the works of others like him, generally grouped together under the name of the Hudson River School, had the effect of changing public opinion toward wilderness and opening the public eye to the beauty and the abiding spirit that lingered in wild forest. Slowly the concept of the value of woodland for spiritual and aesthetic qualities rather than economic worth began to seep into the American mind, and within the next few decades the new nation began setting aside vast tracts of open space, known as “national” parks, the first such land designation in the world. These parks were followed over the next century by uncountable areas of public and privately held plots of land that would be maintained—in the words of the charter of one of the great American forest preserves—“forever wild.” The Great God Pan, were he with us now, might feel right at home here. JHM |